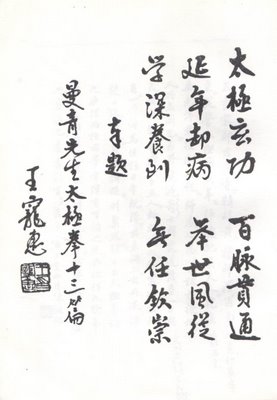

Song of Taichi Chuan: Music by Lu Su, Words by Cheng Man-ch'ing 2nd

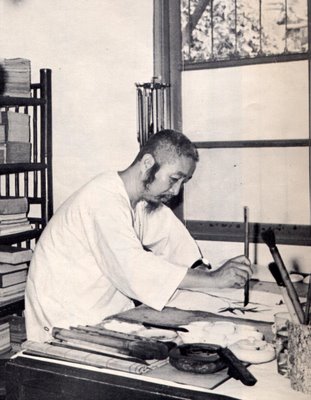

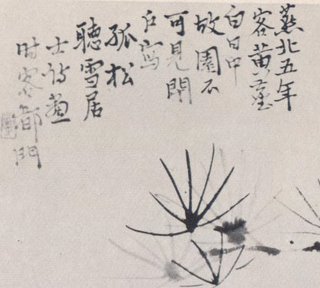

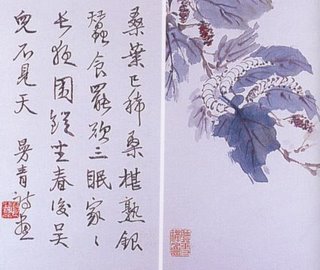

Add another talent to the growing list of talents exhibited by Cheng Man-ch'ing: lyricist. Though this one is surely not an excellence. No, I do not mean Sung Dynasty "lyric" poetry (he already has a book of those.) I mean lyricist as in Oscar Hammerstein and Lorenz Hart.

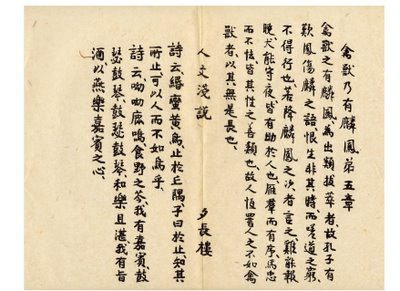

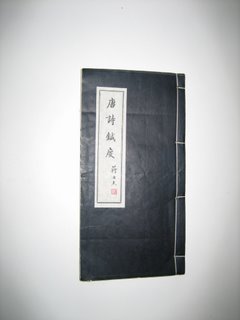

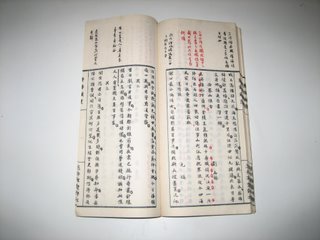

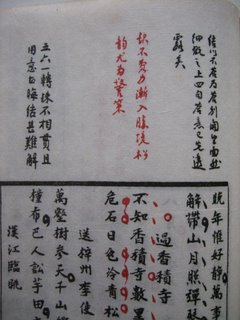

The Song of Taichi Chuan, for very good reasons, was never published in the 1981 North Atlantic version of Cheng's Simplfied Mthod of Calisthenics for Health and Self Defense, though the English version printed in Taiwan still reprints the song.

From a professional musician’s point of view, the song is a pathetic piece of musical triteness. Sure, it possesses a sprightly rhythm reminiscent of that Communist Chinese immortal tune, “Let’s All Work for the Five Year Reconstruction Plan.” And yes, it does contain the eloquent depth of the Kuomintang ditty, “Communist Bandits, Beware Chiang’s Return!” The second phrase in Cheng's song, "You will become good health and happiness," can only really be appreciated when one tries to fit the words into the music.

Then there is the question: Who the heck is the lyricist Cheng Man-ch'ing 2nd? Why has his lyrics been inexplicably excised from Cheng’s American edition? Why was the American public been unaccountably shielded from the detrimental humorous effects of this opus?

More importantly, who excised the authorized song from the American edition? Who authored the excised song? Who exercised their authority? Who authorized the excision?

Pressing questions, to be sure.

I await a competent choral of taichi enthusiasts to rehearse and record this long forgotten favorite and make the ensuing recording available via the internet, for the good of the nation !

P.S. If the jpeg image of the song is illegible, consider yourself fortunate and delve no further. According to one Cheng disciple in SF, most of Cheng's works were "never intented for viewing by the American audience." On this one point I just may agree with him.